Nasim Afsar is a healthcare executive and the former Chief Health Officer of Oracle, the COO of UC Irvine Health, and the Chief Quality Officer of UCLA Health. D.A. Wallach is a rock musician and investor who co-founded Time BioVentures, a life sciences and healthcare investment firm.

Healthcare today is plagued by variability that directly impacts patient lives and health outcomes. Despite advances in medical science, discrepancies in care standards lead to preventable deaths and complications, often disproportionately affecting vulnerable populations. The pace of biomedical discovery has accelerated dramatically, yet the "refresh rate" for implementing new evidence remains painfully slow. This gap highlights the urgent need for a universal standard of care that can dynamically integrate the latest research while reducing the lag between discovery and implementation.

Why Now?

The need for a universal standard of care is more profound today than ever before. The exponential growth of medical knowledge has long surpassed the individual’s ability to synthesize and apply new information effectively. Advances in drug development, medical devices, genomics, and wearables continue to generate unprecedented amounts of data. And for the first time, AI and generative AI could enable us not only to process this vast information, but also to translate it into actionable insights in real time through software, revolutionizing decision-making and patient care.

Persistent workforce shortages in healthcare exacerbate the need for such innovative models of care delivery. AI-powered clinical decision support, remote monitoring, and automation can allow mid-level providers, community health workers, and a broader group of skilled professionals to extend high-quality care under the supervision of digital and human experts. This approach can bridge critical gaps in access, ensuring that care reaches underserved populations without sacrificing quality or safety.

These technology breakthroughs are arising as our healthcare paradigm shifts from reactive “sick care” to a proactive “wellness” orientation, requiring a new framework that ensures consistency in personalized preventive strategies, screening, early interventions, and chronic disease management. Since healthcare now transcends traditional care delivery settings - encompassing everything from gyms to grocery purveyors to an ever wider array of consumer products promising healthy lifestyles - this new framework must be extensible to the whole of the patient’s life experience. Without a universal standard of care, this dream of high quality, affordable precision medicine for all will fail due to fragmentation, inefficiency, and disparities.

Critically, a single worldwide standard of care should be available to every person on the planet, as there is no biological basis for delivering different medicine to patients simply because of their locations. Differences driven by genomic and other physiologically relevant variables —which can transcend geography—are of course essential, ensuring care is personalized to each individual’s unique biology. But a patient should receive the same high-quality care whether they are in a hospital in New York or a clinic in Nairobi. While we recognize that vast disparities in economic resources and health system capabilities will not immediately permit a single global standard in practice, it is important to acknowledge that this is a moral failure of our system instead of pretending that different standards are defensible.

Dynamic by Design

Medicine, as a science, must strive for a dynamic consensus: a unified yet adaptable standard, rigorously grounded in evidence, that evolves with new discoveries while safeguarding against groupthink and vested interests. Such a standard is a critical ingredient in rebuilding the public’s respect for medicine and the professionals who deliver it.

The lack of a common language and standard of care would be unacceptable, and at times lethal, in other industries. Imagine if every airport around the world used a different language, different flight rules, and different interpretations of safety protocols. A pilot flying from New York to Tokyo would have to relearn the system mid-flight—different approaches to turbulence, different ways to interpret weather data, different meanings for common commands like hold position or clear to land. The result would be chaos; planes would collide, landings would be unsafe, and the entire global aviation system would break down because there was no universal standard to ensuring seamless handoffs.

In healthcare, we are effectively flying without that universal standard. It’s time to change this.

Today's medical standards of care owe much to the foundational evidence generated by traditional randomized controlled trials (RCTs), which have shaped the clinical guidelines we rely on today. However, as medicine evolves at an unprecedented pace, we now have the ability—and the responsibility—to complement this evidence with real-time data from diverse sources. Rather than treating standards of care as static rules, we can transform them into dynamic, continuously updated frameworks that integrate emerging research, clinical insights, and population-level trends. By incorporating real-world patient experiences, AI-powered predictive analytics, and evolving epidemiological data, we can ensure that standards of care are not only evidence-based, but also evidence-responsive—enabling healthcare providers to make the most informed decisions in the moment, ultimately driving better patient outcomes.

The reliance on double-blinded randomized controlled trials (RCTs) as the gold standard for changing clinical guidelines creates a significant bottleneck in the evolution of care. While RCTs provide invaluable insights, they are time-intensive and often miss the complexities of real-world patient populations. Meanwhile, vast amounts of real-time data from electronic health records, wearable devices, and AI-driven pattern recognition tools are available, revealing evolving trends in disease prevalence and treatment responses. Unfortunately, these insights are often ignored or underutilized in shaping medical standards. As a result, the healthcare system remains reactive rather than proactive, failing to leverage technology’s full potential to accelerate medical progress and improve patient care.

A striking example of this failure is colorectal cancer screening guidelines. For years, the recommended screening age was set at 50, based on older population data. However, as colorectal cancer rates in younger individuals began rising, real-world evidence showed an alarming trend—more people in their 40s, and even 30s, were being diagnosed and dying from the disease. In response, the screening age was lowered to 45, yet this adjustment still lags behind the reality of shifting epidemiological patterns. Many individuals under 45 continue to develop aggressive colorectal cancer, yet current screening recommendations do not adequately account for this evolving risk. This rigid, incremental approach to changing standards fails to respond dynamically to real-world data, leaving countless patients undiagnosed until it is too late. Once they are diagnosed, they too-often receive variable care. A universal, adaptive standard of care—continuously updated with real-time data—would prevent delays in necessary interventions and save lives.

Beyond Practice Guidelines

Today, medical knowledge takes multiple different forms depending on the context: textbooks of physiology, continuing medical education curricula, pharmacology compendia, and so forth. The form factor closest to the standards we envision is a “practice guideline.” A universal, evidence-based standard of care must begin with a framework or “ontology” of medical decision-making. Decision-making is an optimal unit of organization for this endeavor because the purpose of a standard of care is to clarify as many medical decisions as possible in the real world. This ontology would cover the widest possible range of clinical decision points—moments when providers must actively choose among diagnostic, therapeutic, or caregiving options. For each decision point, the standard of care would specify the range of acceptable options, the evidence supporting each, and the conditions under which one option might be preferred over another. To the extent that decisions are best made by applying algorithmic calculations, the standard would clearly explain these. This approach would ensure that every decision, from routine care to complex interventions, would be guided by the most rigorous evidence available.

In diagnosis, a universal standard of care would function as a set of situation-specific algorithms designed to optimize differential diagnosis using Bayesian principles. By guiding providers to collect and analyze the most relevant information in the most efficient sequence, these algorithms would minimize unnecessary testing and accelerate the path to definitive diagnoses. Similarly, in treatment, standards would guide the selection among interventions to maximize success and minimize harm. For routine caregiving, the focus would shift to formalizing best practices that prioritize safety and enhance patient experience.

To be truly effective, these standards must be both computable and human-readable. On the one hand, they must be discrete and unambiguous to ensure seamless integration with computational systems, such as AI-powered diagnostic tools or decision-support software. On the other hand, they must remain accessible and interpretable for healthcare providers and patients alike, fostering transparency and shared decision-making.

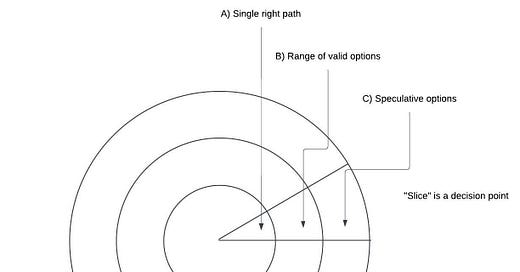

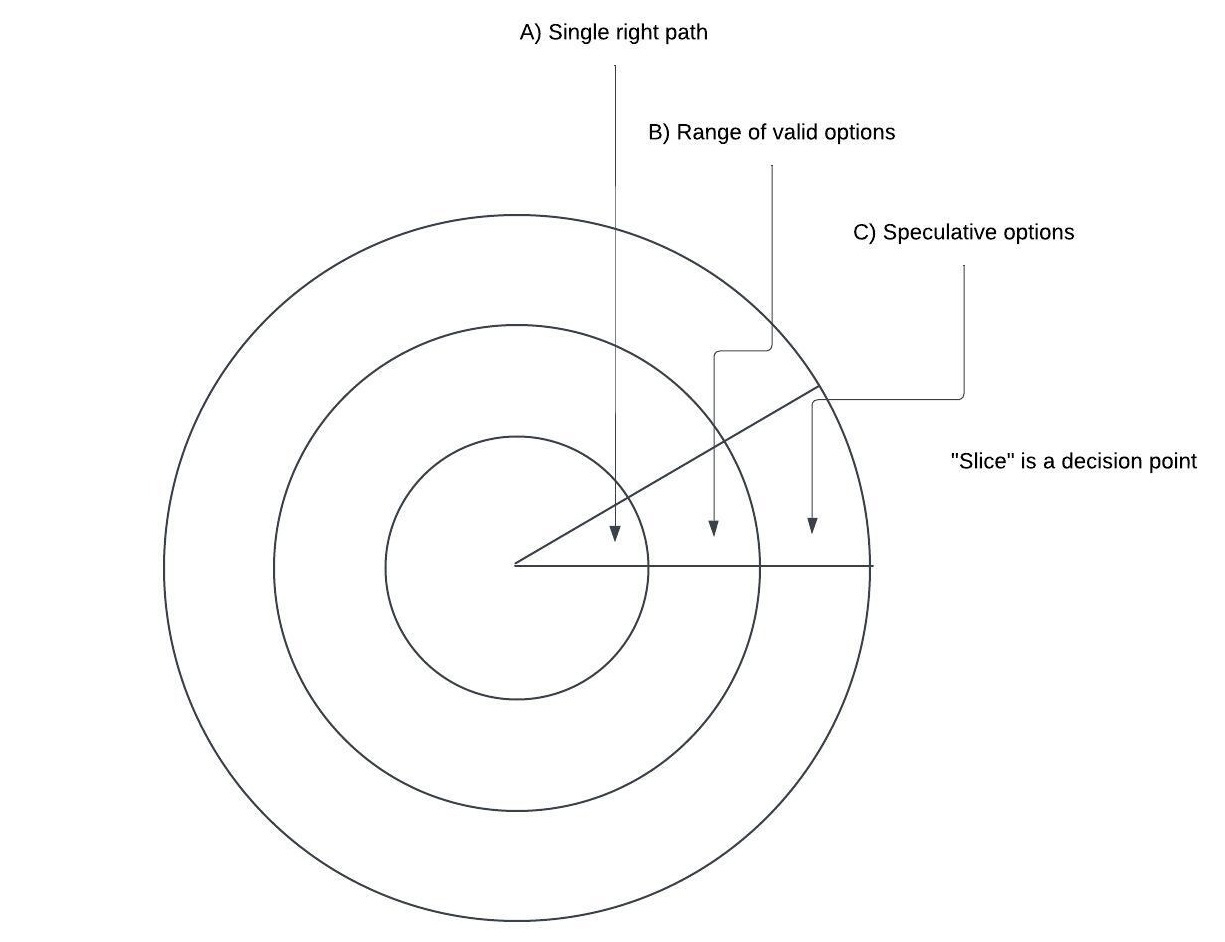

A robust standard of care must also accommodate the evolving nature of medical knowledge. It can be envisioned as a set of concentric circles (example below), with the innermost circle encompassing universally agreed-upon practices that apply “always and everywhere.” The middle circle would include standards reflecting reasonable uncertainty due to varying values or conflicting evidence, while the outermost ring would cover speculative or highly contested practices. For any given clinical scenario, physicians and patients should be able to access a “slice” of this framework, contextualized to their specific needs and circumstances. This dynamic, layered approach ensures that universal standards remain adaptable to both current evidence and future innovations, paving the way for equitable, efficient, and patient-centered care worldwide.

A Benchmark for Real-World Activity

A universal standard of care would not only guide clinical decisions but also redefine medical errors and their consequences. Malpractice would have new precision and clarity. It would be formally defined as any deviation from the innermost circle of universally agreed-upon practices, or from the range of acceptable options in the second circle if no inner-circle standards exist. This clear delineation would give patients and providers a shared understanding of when care has fallen below acceptable standards, fostering accountability and trust across the healthcare ecosystem. Unfortunately, today’s malpractice standards are ill-defined and typically depend upon “expert” testimony and “he-said she-said” accounts of care. With technology that we already have today, accurate records of patient care could be generated using AI-based documentation from video footage of all clinical encounters. By comparing these records to the universal standard of care, significant ambiguity could be eliminated in determining whether the standard was met.

We have mentioned that the standard should evolve as rapidly as the pace of new evidence, and real-time AI-based documentation of real-world medical practice facilitates this. By collecting this real-world evidence everywhere and at all times, we can generate accurate data , allowing researchers to compare outcomes across diverse populations and settings. This evidence can highlight disparities between published data—often limited by selection bias—and actual patient outcomes, enhancing our understanding of healthcare delivery.

Furthermore, a standard allows for systematic study of deviations, turning them into opportunities to discover new or improved methods of care. The goal of a single standard is not to discourage innovation or rigorous physician judgments; rather, it is to require that when physicians proactively deviate from the standard, they document the rationale for doing so and ensure that their patients understand that they are together choosing an different approach. A paradigm for experimental medicine exists already in the world of clinical trials. Patients in trials know what they are signing up for, whereas patients in traditional care who are being given non-evidence based care today have no idea. Without a defined standard and baseline, patients will remain in the dark and novel insights will remain elusive.

By creating a shared framework, a universal standard also enables healthcare providers and systems to identify why best practices are not consistently followed. Whether due to resource constraints, lack of provider education, or systemic inefficiencies, understanding the root causes of non-compliance allows for tailored, scalable solutions. Importantly, this framework fosters alignment across a fragmented healthcare ecosystem, from academic medical centers to retail clinics and startups, uniting all stakeholders under a common goal of delivering safe, high-quality care.

Ultimately, this approach establishes a unified, evidence-based foundation for healthcare that not only clarifies malpractice but also drives innovation, equity, and collaboration on a global scale.

A Blueprint for Action

Creating a universal standard of care begins with a focused, practical approach that prioritizes impact and feasibility. By concentrating initial efforts on 10 to 20 of the most common conditions, we can establish a strong foundation that delivers immediate benefits across diverse areas of healthcare. These conditions should span three critical domains: preventive care, such as cancer screening and prevention; chronic disease management, addressing widespread conditions like COPD, heart failure, diabetes, and cancer; and acute care, with a focus on emergencies such as heart attacks. Starting with these high-impact areas ensures that the standard addresses the needs of a significant portion of the global population while generating early momentum for broader adoption.

Central to this initiative is the creation of a centralized, interoperable repository that serves as both a source and destination for evidence-based practices. This repository would disseminate the latest standards globally, ensuring that healthcare providers, regardless of geography or resource constraints, have access to up-to-date, actionable guidance. Additionally, interoperability would allow the repository to collect performance data from diverse care settings, enabling real-time feedback on the effectiveness of the standards and identifying areas for improvement. This dynamic exchange of information would ensure the standard evolves in step with new discoveries and real-world insights.

Building this framework requires close collaboration among stakeholders across the healthcare ecosystem. Policymakers, clinicians, researchers, and technologists must work together to define and validate the standards for each decision point, ensuring they are both rigorous and practical. The process must also include input from patients, who can provide critical perspectives on feasibility, accessibility, and equity. Once developed, these standards must be rigorously tested in pilot programs across varied care environments to refine their implementation and ensure scalability.

The universal standard of care is not a static set of rules but a living framework that must evolve with medical advancements. By leveraging advanced technologies, such as AI and data analytics, this system can provide decision support at the point of care while also identifying emerging trends and gaps in adherence. As standards are updated, the repository can seamlessly and instantaneously disseminate changes to all stakeholders, ensuring continuous improvement and alignment with the latest evidence. The goal of this model should be “update once, implement everywhere, instantly.” This would ameliorate the often decades-plus delays that exist today between new evidence and implementation, during which patients suffer from antiquated care.

Barriers to Overcome

While the vision of a universal standard of care is compelling, its realization faces several significant barriers, starting with the question of ownership. Determining who will house and oversee this global framework is a fundamental challenge. Should this responsibility fall to established international organizations like the World Health Organization (WHO) or the United Nations (UN)? Or should it involve a coalition of regional and national healthcare bodies working collaboratively? The answer will require balancing the credibility and resources of global institutions with the need for local adaptability and stakeholder trust. Without clear ownership, the initiative risks fragmentation and lack of accountability, undermining its goals.

Furthermore, health data can be considered a matter of national security, and some may perceive sharing information with a centralized global body as a potential risk. To address these concerns, a phased approach can be adopted. Phase I would involve each participating nation developing its own centralized standard of care, ensuring national sovereignty over sensitive health data while improving consistency within borders. However, for global interoperability, a universal framework must be established—an agreed-upon set of guidelines for structuring, integrating, and securing health data across systems.

In Phase II, once national systems have matured and proven effective, their data can be securely aggregated at an international scale, leveraging anonymized, de-identified records to drive global disease surveillance, predictive modeling, and coordinated public health responses. This phased strategy ensures that national security concerns are balanced with the imperative of harnessing collective intelligence to improve health outcomes worldwide. Without such an approach, we risk perpetuating a fragmented, inefficient system that continues to lag behind the potential of modern technology and medical advancements.

Adoption of the universal standard by healthcare systems and organizations is another critical hurdle. Why should disparate healthcare groups, each with its own priorities and operational models, align with a global standard? The answer lies in framing the standard as both a social contract and a public good. By ensuring that a child in Rwanda receives the same high-quality care as a child in New York City, the universal standard addresses global healthcare inequities and aligns with the ethical imperative of equitable care. At the same time, the individualistic argument is equally powerful: patients everywhere want assurance that their loved ones will receive evidence-based, high-quality care, whether they are at home or traveling abroad.

However, achieving buy-in across such a wide spectrum of stakeholders requires addressing practical and philosophical concerns. Healthcare systems and physicians may fear losing autonomy, while private organizations may resist changes perceived as a threat to profitability. Governments, particularly in resource-constrained settings, might hesitate to commit to a framework that could strain their budgets or require significant infrastructure upgrades. Overcoming these objections will necessitate emphasizing the long-term benefits: improved patient outcomes, reduced variability in care, and cost savings achieved through standardized best practices.

Cultural and geopolitical differences further complicate the adoption of a universal standard. Healthcare priorities vary widely based on local disease burdens, societal values, and economic conditions. For example, a preventive care standard for cancer screening may resonate in high-income countries but feel disconnected from the immediate needs of low-income regions grappling with infectious disease outbreaks. Striking the right balance between global consistency and local relevance will require careful consultation and adaptation to ensure the standard is both inclusive and impactful.

Finally, the initiative must contend with skepticism and resistance from individuals and organizations accustomed to entrenched practices. Building trust will require transparency in the creation and governance of the standard, with open dialogue among stakeholders to address concerns. By framing the universal standard of care as a shared commitment to equality and excellence, its proponents can build the consensus needed to overcome these formidable barriers and drive global healthcare transformation.

Conclusion

The creation of a universal standard of care is not merely an ambitious vision; it is an urgent imperative in a world where healthcare variability continues to cost lives. By defining clear, evidence-based practices for common conditions and leveraging technology to disseminate and update them globally, we have the opportunity to transform healthcare delivery for billions of people. While barriers such as governance, adoption, and cultural differences must be addressed, the potential benefits—equality in care, improved outcomes, and a unified healthcare ecosystem—far outweigh the challenges. This endeavor is a moral and practical necessity, ensuring that every individual, regardless of geography or circumstance, receives the high-quality, evidence-based care they deserve. The urgency of this work cannot be overstated; the time to act is now, for the sake of current and future generations, to whom we can leave a world in which the extraordinary benefits of medical knowledge and technology are available in equal measure to all people.

This is definitely where humanity is going, and where it will end up. Universally (almost) lists of essential medicines for treating prevalent conditions is an extant stepping stone in this direction. RBCDB studies will be run on thousands of genomes in silico vastly accelerating the availability -- and known limitations -- of new molecules to treat literally thousands of diseases.

I love this concept! One thing I keep thinking about- what could be done to account for difference in resources among geographies- e.g. availability of CT scans, labs, skilled providers performing diagnostics e.g. colonoscopy..